THE ORCHESTRATION OF THINGS AND OCCURRENCES OF EVERYDAY LIFE

Notes on some of Aïcha’s images

No doubt, Aïcha has experienced a lot. And she has embarked on painting. More on how the two are connected later.

Aïcha paints, mostly in large format and on wood. She uses pigments, aqueous binders and also latex, acrylic paints along with chalks. The paints are applied thinly, almost like watercolors. Aïcha paints directly in one go. Her paintings are straightforward – they are characterized by a deep authenticity in terms of their rootedness in the artist’s biography. The figures in her most recent works are life-size, adding a dialogical dimension to them: the protagonists of the paintings and their viewers meet at eye level. And quite often there is a resonant psychologizing undertone. For instance, the gaze of a woman in a black maid’s costume – we see Odette, the domestic help – wanders off into the distance; and at the same time her facial expression is turned inward, by all means a little stern, as if the figure were completely and only within herself, perhaps full of pride, but perhaps also weary of life. She is perched on a landing. Unwavering. With palpable weight. Sculptural. Her hands, stuck in blue rubber gloves, lie folded in her lap. The fact that the window behind Odette offers no view further intensifies the situation of gaze and counter-gaze and evokes a sense of hopelessness. The picture tells of a strong woman in the shadows …

And quite often there is a resonant psychologizing undertone.

No doubt, Aïcha has experienced a lot.

Michel et Elle – a double portrait and, incidentally, the first portrait by Aïcha – is composed in a comparable manner. We see two people in the middle of an interior where spatial depth is reduced to a minimum. The figures are embedded like inlays in color fields that represent the floor, wall, moldings, a round side table, and the play of light effectuated by the window. While the man is identified as a peasant from Normandy by the inscription “Michel” on his blue overalls, the identity of the female figure indeed remains vague. Is she an effigy of Michel’s wife, his grandmother, a self-portrait of the artist – or perhaps a little bit of all of them? Are we to see the woman in the image as the artist’s accomplice?

Distinctive in terms of painting, her facial features are framed by a picture frame on the back wall and thus staged as a picture within a picture.

This underlines the isolated juxtaposition of the two figures, the impression that nothing connects them, probably least of all positive emotions. Both sternly stare ahead. Michel’s hands are stuck deep in his trouser pockets as if sewn into them. He comes across as a taciturn curmudgeon or grump, who, like other men of his ilk, likes to down another glass of schnapps on the injustices of a world in which you only had to take what you passionately desired. Michel, whose wife’s name was Chantal, was Aïcha’s foster father when she was young.

Orange, pink, greenish ocher, brownish cadmium red … light pink, brownish orange, bluish light gray, pink and pink – the individual tiles of a kitchen floor are loosely painted. On the gray-blue wall of the kitchen an orthogonal field of bright orange tiles, the grout lines bright red. What a rush of colors! Painting of the highest order! In between, brown sections suggesting the legs of the kitchen table, as if they too were part of the floor. And on the table? A still quite full bottle of pastis of the Ricard brand. And a full glass, gripped by the hand of a somewhat bloated woman. It is Chantal, Michel’s wife, seated next to the table on a chair, of which hardly anything is still visible. To the left and right of her head a little bit of backrest and a cross brace between her calves, nothing more. Such a most intimate degree of privacy in this painting! You wouldn’t ever want to expose something like this of yourself even to your best friend. The woman’s feet – she is wearing a rather simple apron dress with modest trim – are immersed in the water of a blue tub. Washing one’s feet in a kitchen and getting drunk at the same time, not at night, but on a sunny day, as the chromaticity of the painting emphasizes. Despite all the lighthearted colorfulness, this is rather tough stuff – where to shall any new beginning proceed from here, how are confidence and trust supposed to grow?

Aïcha’s earlier paintings manage without figures. It is tempting to suggest that they are a bit rougher and bulkier than the more recent works. This is due to their almost brutalist pictorial spaces. They are also less color-intensive, a touch gloomier still.

Such a most intimate degree of privacy in this painting!

Aïcha’s earlier paintings manage without figures.

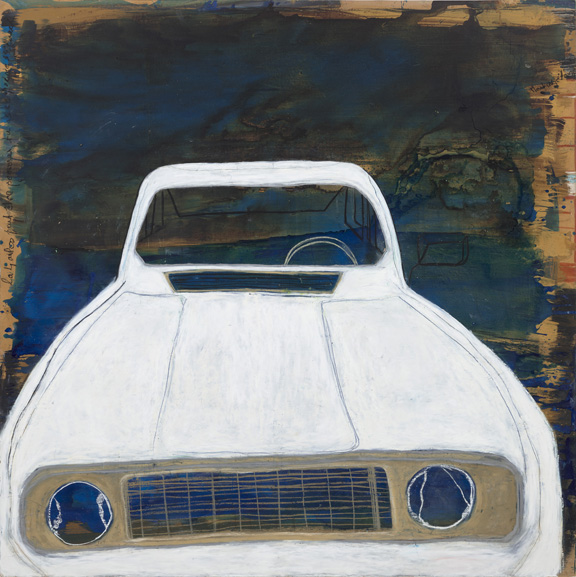

The front view of a white painted R4, for instance, is fitted into the quadrangular image area in an ever so slightly asymmetrical way that a sheet of paper would hardly fit between it and the edge of the picture. Radiator grille, hood, air vent, windshield, and steering wheel – the rest of the interior is only hinted at graphically. All the details are stacked up rather than their arrangement suggesting depth or space. A great image of a “people’s car” that, like the Citroën 2CV, also from France, or the Beetle from Germany, embodied the petit bourgeoisie’s dream of mobility and freedom from the 1960s onward … And then there’s the bus. It, too, is completely flat and placed parallel to the edge of the image. Its color scheme is audaciously balanced with contrasting warm and cold green tones. The light and dark portions of its windows create a subtle rhythm. The way they sometimes offer a view through and then again not, follows less an inner logic than a thoroughly playful intuition. The fact that the sun, indicated by a bright yellow graphic abbreviation, bears the numbers “1 2 3” suggests that Aïcha, like children everywhere, spent her time waiting for the school bus with the hopping game of hopscotch, which in French is actually known as 1, 2, 3 soleil. In fact, the left panel of another, two-part painting shows such a hopping game outline, next to it there is an inflatable children’s pool filled with water. Its colors are a vibrant blue. A green water hose snakes over to the right panel as a connecting link, ending there midway at a building – an architectural curiosity in rural northern France. One half is a town hall accessible to the public, identified by the inscription “MAIRIE” above and by a small French tricolor next to the entrance, the other half, recognizable by geraniums hanging in front of the window, is a residential house and as such a former place of retreat also for Aïcha.

Aïcha paints against the background of her own life story. In her pictorial worlds, she returns to her childhood and youth. She reflects dreams and desires and occasionally even creates romantic sceneries. She orchestrates the things and tragedies of everyday life. The room of her childhood was austere and dark (La chambre de mon enfance is the title of the painting). While a mouse plays a high-risk game with a trap at the foot of a metal bed, a medicine bottle and especially the accompanying words “INSOMNIE – ANXIETE – NERVOSITE” (Insomnia – anxiety – nervousness) also identify the child’s room as a sick room, leaving the viewer to wonder if an entire childhood was spent there in a state of anesthesia? A picture of another bedroom, this time probably in a children’s home: “INTERIEUR EXTERIEUR” – inside outside – reads one of its inscriptions. A white and blue striped curtain, trimmed at the top with a valance, is tied to the sides in a bouffant way. Merely hinted in between is a white window cross. From the outside, we look into a narrow, but colorfully furnished interior. The bed gleams in pink and has just enough space in the room next to a small open area in front of it. Its upper end is flanked by a green and black framework, which, elaborately painted, corresponds with the calm surface of the rose-colored bed. The entire bed colored in pink – does the scene symbolically represent the realm of innocence that had been lost? Yet what is often forgotten in this context is that even paradise, where there was no sin to begin with, still was the most beautiful of all prisons known to us, the gated Garden of Eden in the midst of an otherwise desolate landscape.

Aïcha paints against the background of her own life story.

I have never said “I love you”

(to my mother)

The shock that Aïcha experienced when, back from school, after only a few days of a personal and supposedly happy rapprochement with her mother, she found her dead after she had committed suicide, is condensed in the image Je n’ai jamais dis je t’aime à ma mère (I never said “I love you” to my mother). In addition to this homage to her mother, there are other paintings by Aïcha that show the locations of events, where we do not see the protagonists in action, but rather only traces or props that provide clues as to what went on. On the one hand, there is the almost frozen-rigid interior, which emerged in memory of the visits to the grandmother on May 1, Labor Day: a large wall calendar clearly indicates the public holiday. The table in front of it is empty and uninviting. The blue smock hangs on the door, underneath is a pair of rubber boots ready to continue in the rhythm of everyday farming life, which is, after all, characterized by animals and plants that do not respect holidays. Their needs have to be satisfied regardless – the world after all is not made of ideas and ideals alone!

A festive day? A wedding is very much considered to be one. Then, as the icing on the cake: the honeymoon. The set and decorated table is inviting for dinner. Champagne awaits, already in glasses. Daisy flowers scattered on the table symbolize fortune and confidence. The image reveals desires and projections, even inner worlds – it is thus altogether romantic. But the point here is less to demonstrate that which we would personally like to experience; rather, it is to show that which is formed as reality through the means of painting. The table cloth of floral lace is painted in a correspondingly refined manner, providing a link between all the other objects and at the same time creating a dream-like atmosphere of the poise between showing and concealing.

The image reveals desires and projections, even inner worlds.

Wild and with tremendous freedom, but at the same time controlled by a profound confidence in terms of painting.

Last but not least, another interior, entitled La Garçonnière. The term in French refers to a modest bachelor apartment. Usually one room only, with an anteroom for kitchen and bathroom facilities. A female-occupied counterpart of the apartment type would probably be called a studio apartment. There is an impeccably white bed in the center of the room, flanked by picture panels with floral-ornamental patterns on one side and a large potted plant on the other. And on the bed, there is a couple. Both dressed well, indeed quite festively. The man in front (the bachelor?), directly behind, towering above him, the woman. One of her arms in long pink gloves lies across his heart, the other on his back. Are we seeing a male muse here? Or does the image suggest a form of twosome loneliness? Is the woman one-sidedly in love (at least more in love than him, who appears to be not genuinely turned towards her), as her gaze and posture might suggest? Or is it, on the contrary, perhaps a happy liaison, since the man’s head is almost inseparably pressed against the woman’s body just below her breasts? In the end, the possible interpretations of the scene remain complex, the painting itself suspensefully mysterious. Seeing the painting at Aïcha’s home – in a traditional Majorcan country house, the artist’s place of residence and work – makes is obvious how everyday things and decor find their way into her paintings as spolia of reality, which in this respect are thus entirely beholden to the here and now. A large potted plant, for instance, is placed in a neighboring room of the house, and the blue ornament that adorns the bottom of the bedspread is found on the tiled landings of the staircase leading upstairs.

Having been in the artist’s house just a moment ago, we then briefly went out. And at the end of the day a female dog then runs the final perhaps one hundred and fifty meters completely of her own free will and with a whimsical, sweeping canter back to the house on her own … It would hardly be a surprise if this dog were soon to appear as the protagonist of one of the artist’s visually powerful works.